I attended the last rOpenSci call on data repositories1 (recording) and below are my two cents on why storing on, and using data from the web may still be such a headache.

The hour-long community call was - as always - inspiring and presented itself in a relaxed setting; with a set of experts voicing their experiences and challenges around data repositories from different angles, and a Q&A session towards the end. It was, however, over way too quickly and when I left the Zoom call I still had these loose ends in my head.

I am by no means a data repository expert, but I have faced challenges in both using data repositories and storing data in repositories while working as a genomic data scientist.

The big picture

Purpose

The advantages of open science have been discussed elsewhere2.

Three reasons why researchers need (to share) data come to my mind:

- Scientific findings; to do research we need data. But even if we have collected and analysed our own data, we often need external data to replicate our results.

- Reproducibility; we may want to rerun results shown in a paper (i.e. check reproducibility of published results).

- Standards; repositories may also guarantee certain data storage standards. If we don’t have governed data repositories, everyone will develop their own standards.

Options

The scientific community has already access to a wide range of data repositories out there: Dryad, Zenodo and figshare. They are fairly easy to use, integrate well with other tools and have free plans.

The enigma

The question is then:

There are these great (and free!) data repository solutions out there AND we clearly need them - how come they are not used more often?

The experts

The experts on the call were the following3:

- Daniella Lowenberg, representing Dryad

- Matt Jones, representing dataONE

- Kara Woo, representing Sage Bionetworks and guiding through the call

- Carl Boettiger, a researcher

- Karthik Ram, a researcher

Culture change & storage as an afterthought

I work in academic research, and two comments resonated most with the problems I am facing, hence I will focus on those:

- Karthik Ram made the point that although there is infrastructure to host code, data, and computing, a) they lag behind in user experience and b) users lack incentives to share their data.

- Carl Boettiger mentioned that analysis and storage are still too far apart, with public data storage being a mere afterthought.

Let’s discuss these two points in turn.

What’s needed for culture change?

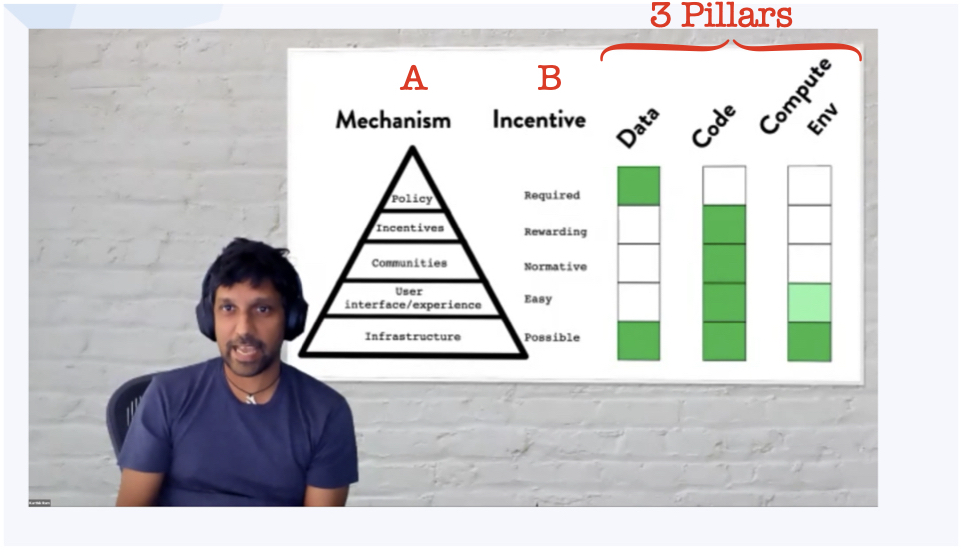

To illustrate where data repositories lack compared to code and computing, Karthik Ram showed the pyramid for culture change introduced by Brian Nosek (shown as an annotated screenshot below).

On the left hand side (A) are the culture change mechanism (along with their incentives B):

- Infrastructure

- UI/UX

- Communities

- Incentives

- Policy

On the right-hand side are the three pillars of (computational) research: data, code and the computing environment.

Green highlighting demonstrates where the mechanism has been accomplished.

All three pillars have the necessary infrastructure, which is the basis of the pyramid of culture change.

Code is almost fully accomplished, with only policy left out (very few journals require code to be supplied).

Computing environment can be shared, at times easily, e.g. through docker containers, but it lacks a community, incentives and policy enforcements.

Now data HAS actual policies. Often journals require data alongside the publication, but for a proper culture change, we would need UI/UX, communities and incentives4 to be present.

git as a model

Karthik Ram mentioned also that git wasn’t always as widely used in research, but now it is. Probably mostly thanks to infrastructures such as GitHub.

So hopefully data repositories will eventually become as popular as the use of git!

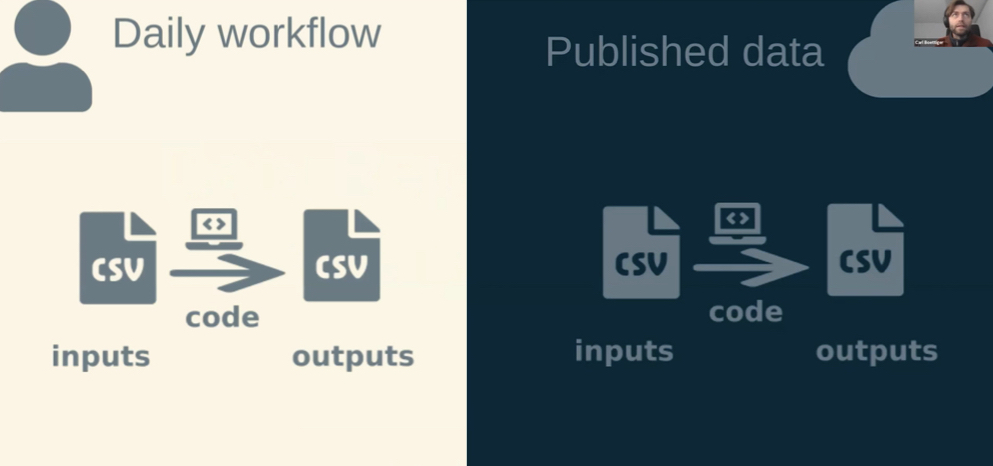

Data repositories as an afterthought

The second comment that got me thinking was by Carl Boettiger: the discrepancy between the daily workflow and publishing the work.

Published data often comes at the end of a lengthy research project, when this is actually quite counter-intuitive (why being at the end when it’s the foundation of a project?).

What’s meant by this? First we collect the data, analyse it using scripts, we get results (which are again data), maybe we write a paper (all displayed on the LHS). After all of that we then think about getting the data (input + results + code) onto a data repository (RHS) - because we remember that this is what we should do.

From Karthik Ram we have learned that some mechanisms for an easy use of data repositories are missing, but that we do have infrastructure to do it and policies that demand it (hence the last-minute panic).

Carl Boettiger also made the point that both - the daily workflow and published data - want similar things5, but that the tools to achieve them are different. In daily workflows we use R, git and data buckets; while published data are dealt with REST APIs and other tools.

Computing environments that can access code and data at the same time

Might the best solution not be to store data + code + computing environment all together somewhere publicly from the very beginning of an analysis?6

This has been proposed by binder, and wrapped into the R package holepunch by Karthik Ram.

A similar solution is to use a cloud computing service combined with a pipelining tool (e.g. cromwell or nextflow). I started to use this setting over a year ago and find it so far the best approach - if the budget allows (cloud computing environments come at a price). I do wonder though, if universities will continue to invest in computing clusters or shift to cloud computing with managed access.

The tricky bits about data & privacy

Let’s now put this all into context with real work and real data: I work mostly with human genomic and health (records) data, with sample sizes ranging from a couple of hundred to hundreds of thousands.

Embarrassingly, it was only in 2018 when I first heard about Zenodo. The reason is, I believe, that free sharing of human data is rather complicated (and in fact prohibited in many situations), as privacy laws apply (Kara Woo mentioned this too). Additionally, as an analyst I am not involved with data collection and therefore other entities decide on whether to store the data in a repository (e.g. the use of dbGAP + EBI) or keep it elsewhere.

To illustrate the extreme measures taken in terms of privacy; the 100,000 Genomes Project from Genomics England has a data center, where remote desktop computers are provided (it used to be a physical data center). And only a selected group of people can access the data.

What can often be shared though is summarized data, called summary statistics. For genome-wide association studies (GWAS) there is an organisation called GWAS catalog, which provides a domain specific data repository for summary statistics only. They do a good job in making it easy to upload summary statistics; they standardize it, they educate people - and yet it may take a while till summary statistics show up there and lots of published summary statistic data are on university servers, google drives or websites (using different data storage standards - which causes lots of extra work for people that want to use the data).

Some ideas

1. Think carefully ahead of time about incentives for analysts

What’s worse? Going through the process of depositing the data in a repository (which means harmonizing the data, adding a data dictionary, sorting out permission, etc.) or dealing with the cumbersome process of finding data again after years of not working on it?

2. Depositing the data online when starting to analyse it

This results in an additional incentive: ensures backup of original base data (if you protect it from write access).

3. Learning from studying other peoples work

Initiatives such as reprohack make participants aware of necessary standards and subsequently enables them to lead by example.

4. Use a hash in file names for identifiability of files

Proposed by Carl Boettiger. This would resolve a notorious problem in my setup. For example, using a standard filename, say dat.txt, may result in overwriting the file with different data, but the same filename. This won’t happen with hashes. As a downside they may be a bit clunky to use.

Yes, it did take me two months to write this up…↩

E.g. https://okfn.org/opendata/why-open-data/ or https://www.nature.com/articles/nchem.1149↩

They have diverse affiliations, but I added the one that seemed to me most fitting in the context of their presentation.↩

I think that there are incentives for storing data in repositories - if people only knew about them! For example I’d say that looking up your own work is much easier with a properly organised online archive - instead of fumbling with outdated server logins and looking through backups.↩

As mentioned above, “find previous work” is one of my prime incentives to use data storage.↩

This was also asked by one of the participants; Michael Summner asked if combining code and data in a public computing environment would solve the problem.↩